The plaster casts Ofthe Royal Academy of Fine Arts

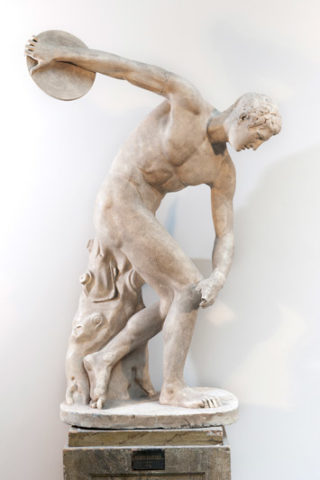

The collections of the Royal Academy of Fine Arts today include almost 800 sculptures, most of them plaster casts used in art teaching in the past. They comprise everything from Michelangelo’s enormous Moses to small plant ornaments intended as inspiration for interiors and design.

About 30 of the largest, and also the most important in art history terms, have been on display in the entrance hall and stairwells of the Academy building since 1890. Some of them, however, have been in Sweden for more than three centuries!

In 1687, palace architect Nicodemus Tessin visited Paris and saw a part of the collection of casts of important ancient artworks that the French king had acquired. They were intended, among other things, to serve as inspiration and guidance for art students. The sculptures were important pedagogic aids for the young artists to make drawings of in order to learn the era’s “canon”. Above all they were to study the ideal of the human body as represented in Greek and Roman antiquity.

Nicodemus Tessin also had plans to found an art academy in Stockholm. Sweden may have been a major power politically at the end of the 17th century, but its art was badly in need of a boost to reach the highest European standard. No country with any measure of ambition could do without a collection of the great ancient masterpieces, as inspiration to its artists and a sign of the education level of its cultural elite.

Due to the succession of wars Sweden fought from 1700 and over more than the following two decades, Tessin never had the opportunity to found the academy on the French model that he had in mind. It wasn’t until 1735 that the Royal Academy of Fine Arts was established – on a modest scale, as a School of Draughtsmanship where the focus was on studies of the human body.

In 1780, however, the expanded Royal Academy of Fine Arts was able to move into its own building, which it had been given as a gift by Gerhard Meyer. A small collection of plaster casts, most of them small-scale, were included in the move. But professors Sergel and Pilo were also given a more enjoyable task.

With the blessing of king Gustav III, the 30 or so large plaster casts that Nicodemus Tessin had nevertheless managed to acquire were added to the Academy’s collection. They had arrived in Sweden in three separate shipments between 1695 and 1700. They had then been placed in storage at Rännarbanan, near Hötorget.

In 1780 it was finally time to begin using them in teaching. Art students diligently made drawings of ancient plaster casts including Apollo, the Laocoon Group, Crouching Venus and the Dying Gaul. In parallel they also studied anatomy, so that they would always be able to weigh reality against the ideal physique. The crowning element of their training was to make studies of live models.

During the 19th century, plaster casts of works from the Italian Renaissance, primarily by Michelangelo, were added to the Academy’s collection. But with the passage of time, art turned away from the traditional, academic and classical approach. Making drawings after ancient sculptures became less important, and the plaster casts gradually lost their function as pedagogic aids.

When the Academy’s building was extended in the 1890s to include all of the city block of Uttern, the magnificent hall with double staircases and a glass-roofed light well was also added. Here the plaster casts were given a new role as decorative and commemorative elements. As visitors pass them on their way to current exhibitions, they are reminded of the Academy’s long history and great significance for art in Sweden.

Eva-Lena Bengtsson, Head of collections and archive

Photo: Leif Mattsson

Translation: Tomas Tranæus